renkli resimler, İngilizce.

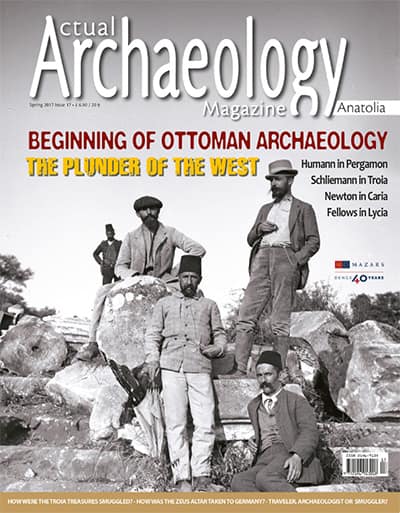

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE'S ARCHIVE IN THE WEST: ANTIQUARIANS

The preparation process of this issue took a long time. It took almost one year to collect all the documents, articles and images. Thousands of documents and images were gathered from German, French and British archaeology institutes in Turkey, as well as archaeology institutes, libraries and university archives in Europe. However, it was impossible to find any documents in the Ottoman archives in Turkey, except in correspondence with foreign committees. It is very sad to see that we do not hold an archive regarding archaeology in the Ottoman territory, especially Anatolia, which has been a venue for the science and history of ‘archaeology’ for almost 250 years. This issue focuses on the last 150 years in that period of 250 years, in other words, the period after the 1850s. The main focus of the issue is the Eastern world in the eyes of Westerners, and during that time the Eastern world was largely formed by the Ottoman territories.

After the Industrial Revolution, the East was rediscovered by Europeans, as this was a source of not only archaeological sites, but also natural reserves, underground and ground sources, etc. The travelers, who started to visit the East, moving from village to village, city to city, from the 16th century onwards, had already collected and published all kinds of information. This was used as an important source of information for the coming centuries. Information regarding the ancient remains also reached Europe through these travelers. In the coming centuries, this information was used in two ways. Firstly, it was used by antiquarians, who collected artifacts for museums in the name of their kingdoms, who established themselves after the Industrial Revolution. Secondly, it was used by scientists, who published works based on measurements and information gathered at that time. In later times, this situation caused confusion in identifying those people who accepted archaeology as a science and the antiquarians. Antiquarians such as Schliemann, Humann, Newton, Fellows, etc. were accepted as collectors at times, and as archaeologists or scientists at other times. However, they were nothing but professional collectors.

The argument claiming that smuggling of antiquities took place in a period when the Ottoman Empire was struggling for its life, can be accepted to a certain extent. During that time, there was no law that could prevent the export of antiquities. Even though Osman Hamdi Bey initially tried to stop this, he did not prevent the export of antiquities, and even gave special privileges that eased the process. The European way of thinking, “If we had not taken, the marble would have been molten in limestone quarries”, is merely nonsense, because we see Ottoman citizens depicted near and around the antiquities in the 16th century travelers’ drawings. The antiquities are depicted intact and unharmed. If these antiquities were in ruins, how would it have been possible to carry them to museums in Europe?

In this issue, our purpose is to correctly explain this period of 250 years, which constitute part of the history of the “archaeological science”, a period of darkness for Anatolia and a period of enlightenment for Europe, and to make a contribution to the creation of collective memory and awareness. For years, Anatolia has been a territory of plunder. Thousands of years of cultural coexistence and remains were commodified in the eyes of Westerners and these artifacts were identified as spoils that would glorify their empires. Today, the most important document we have is the Ottoman constitution of 1876, which was the first constitution of the Ottoman Empire and which restrained the sultan’s will. This subject needs to be thoroughly researched and if this document can be validated, it could be possible to apply to international courts in order to cancel all permits that allowed the export of antiquities.

Have a Nice Read!

Ayse Tatar